From: zerohedge

Dollar demand for trade, FX reserves and cross-border credit has remained weak despite lower prices, underscoring that the US currency’s hegemony has peaked.

It’s become fashionable of late to predict the demise of the dollar. The US’s weaponization of its currency and the rise of China has led many to write the USD’s epitaph.

But as Oscar Wilde remarked, the truth is rarely pure and never simple. The dollar is going through a transition, but it is one that will be gradual. It is not about to be, or likely to be any time soon, supplanted by another currency. But there are mounting signs its luminescence has peaked, and we are moving toward a more multi-polar world.

When we say the dollar’s hegemony has peaked, we should be clear about what we mean. Hegemony is not about price, it is about the dollar’s place in the global financial and economic system. With the currency accounting for 40% of export invoicing, 45% of cross-border bank claims, 60% of FX reserves and 90% of FX transactions, it will take years before it’s dominance is seriously challenged.

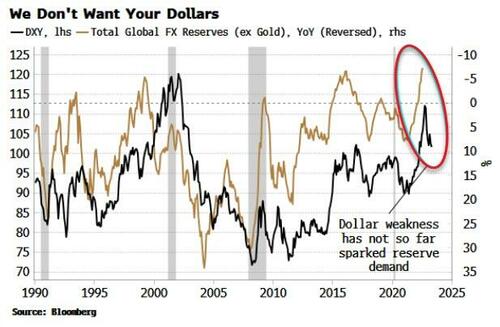

Nonetheless, that process looks to have started, as following four charts demonstrate. In short, demand for the dollar is not rising as it normally would in response to the currency’s near-10% decline since October.

The first chart shows this clearly.

Typically, declines in the dollar coincide with greater demand for FX reserves, as other countries try to limit their currency’s appreciation. But this has singularly failed to happen so far in this cycle. That corroborates the narrative of especially EM countries desiring to lessen their exposure to dollars should they ever face Russia’s fate and see their reserves frozen.

This is emphasized in the next chart of dollar-denominated credit to EMs. After decades of steadily increasing, it is now falling at the fastest annual rate yet seen outside of the GFC.

We are also seeing dollar aversion in commodities. Almost all major commodities are traded in US dollars. Therefore its gains and losses tend to depress or stimulate demand for commodities and thus impact their price.

But the recent fall in the dollar has not stimulated any extra demand for commodities or led to higher prices. This is not to say commodity prices will not rise – the key message is that they have not already done so.

Of course, depressed commodity prices may also have to do with the state of global demand, but world growth is not especially weak at the moment, while liquidity indicators suggest we are on the cusp of a global cyclical upturn.

Either way, this chimes with the narrative that countries such as China, India, Russia, Saudi Arabia and others are moving away from a dollar-centric trading system (with, for instance, ruble-yuan trade increasing eightfold since early 2022).

Also unusual is the behavior of cross-border banking claims denominated in dollars. The chart below illustrates this “dollar structural short.” When the dollar begins to rise, it ultimately forces weak borrowers to deleverage, which they must do by buying dollars to pay back lenders. Normally, some of the deleveraging is reversed once the dollar begins to weaken again, but that has materially failed to happen so far: instead there has been further deleveraging despite the dollar’s selloff.

From a tactical standpoint, the dollar is likely to remain in a medium-term downtrend (notwithstanding debt-ceiling shenanigans which are currently giving a bid to the currency, and position-covering risk from speculators’ net short).

That downtrend can be seen in the real yield curve, one of the best leading indicators for the dollar. This gave a strong indication it was about to peak in October. The curve continues to trend lower suggesting the dollar should keep doing likewise. Several other reliable leading indicators for the currency give the same message.

Whether continued dollar weakness will eventually kick-start demand for dollar-denominated reserves, credit and commodities remains to be seen. But the lack of reaction so far is telling.

It will not be easy for any other currency to step into the dollar’s big shoes. Deep and liquid capital markets, an absence of capital controls, and a willingness to accommodate the rest-of-the-world’s imbalances are prerequisites for global-reserve status. No other country or region is currently in a position to do that.

But it is becoming clear that even though the US currency will retain its dominance for a while yet, the international order is changing, and the dollar’s role within it.